Tortoises and Turtles of the Galápagos Islands

Giant Tortoises

Of the 20 species of endemic reptiles in the Galápagos Islands, these slow giants are the most famous. They also gave the islands their name—galápago is an old Spanish word for a saddle similar in shape to the tortoise shell. The tortoises are found only on the Galápagos and, in smaller numbers, on a few islands in the Indian Ocean.

They reach sexual maturity at about 25 years and are not fully grown until age 100, reaching 1.5 meters (4.9 ft) in length and weighing up to 250 kilograms (551 lb). Many live to the age of 160, although nobody knows their maximum age for sure.

The shell of a giant tortoise reveals which island its owner originates from. Saddle-shaped shells evolved on low, arid islands where tortoises needed to lift their heads high to eat tall vegetation, while semicircular domed shells come from higher, lush islands where vegetation grows closer to the ground. The vice governor of the Galápagos boasted to Charles Darwin that he could distinguish the island of origin of a tortoise by the shape of its shell—just one piece of evidence that helped Darwin form his theory of evolution.

The tortoises’ famous slow, languid demeanor is what allows them to live so long, and perhaps we should all take a cue from them and slow down a little. They spend 16 hours a day sleeping and are most active in the early morning and late afternoon. With minimal movement, their metabolism slows significantly, and digestion takes 1-3 weeks, allowing them to survive with very little food and water during the dry season. When the rains come, the tortoises come alive, eating, drinking, mating, wallowing in pools of water, and sleeping contentedly in large groups. They feed on a wide variety of plants, particularly opuntia cactus pads, fruits, water ferns, and bromeliads.

The only time tortoises make much noise is during mating season, when their unearthly groans echo for long distances. Males become surprisingly aggressive, pushing each other and rising up on their legs to stretch out their necks in a battle for dominance. The shorter male will usually retreat, while the larger male will ram a female’s shell and nip her legs before mounting her from behind and bellowing. The process is long, arduous, and fraught with problems—males sometimes fall off and have great difficulty righting themselves.

When her eggs are ready to hatch, the female will journey for long distances to find dry sandy ground, usually on or near beaches, to dig a 30-centimeter-deep (12-in) hole to bury the eggs, which hatch in the spring after about four months. The temperature of the nest has a marked effect on the gender of the hatchlings: Lower temperatures lead to more males and warmer temperatures to more females.

Of the original 14 subspecies, 10 remain, and 3 subspecies (Santa Fé, Floreana, and Pinta) have been hunted into extinction. One species (Fernandina) was thought to be extinct until scientists discovered a lone female in 2019. Indeed, the giant tortoise population has plummeted from some 250,000 before humans arrived to just 20,000 now. Sailors used to be the tortoises’ main enemy, taking them on long voyages as sources of fresh meat (the tortoises took up to a year to starve to death). Today, the main danger comes largely from introduced species: Pigs dig up nests, cats eat hatchlings, and goats and cattle eat the vegetation and cut off the tortoises’ food supply. It’s not all bad news, however, because there is a comprehensive rearing program to release tortoises back into the wild, most recently on Pinta Island.

It’s hard to visit the Galápagos without hearing about “Lonesome George.” The Pinta Island tortoise was widely regarded as extinct until the discovery of a single male on Pinta in 1971. All attempts at breeding were unsuccessful, leading to his moniker “Lonesome George.” Over the years, as the last of his species, he became an icon for conservation. Fishers famously held Lonesome George for ransom in activism for fishing quotas in the Galápagos. After his death in 2012, his body was meticulously preserved and exhibited in international museums before it returned to the Charles Darwin Research Station.

Five of the remaining subspecies are found on the five main volcanoes of Isabela, and the other species are found on Santiago, Santa Cruz, San Cristóbal, Pinzón, and Española.

Where to See Giant Tortoises

Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz is the most famous place to see these amazing creatures. There is a breeding center with 10 subspecies. Visitors used to be able to walk among the tortoises, but now you must observe from outside the walled enclosures. Lesser known but with a larger population is the Centro de Crianza breeding center on Isabela, which also has several species, and there’s a tortoise enclosure at Asilo de la Paz on Floreana.

To see tortoises in a semi-natural environment, check out La Galapaguera, a reserve and breeding center on San Cristóbal where tortoises reside in 12 hectares of dry forest. Alternatively, wander around El Chato Tortoise Reserve, which fills the entire southwest corner of Santa Cruz.

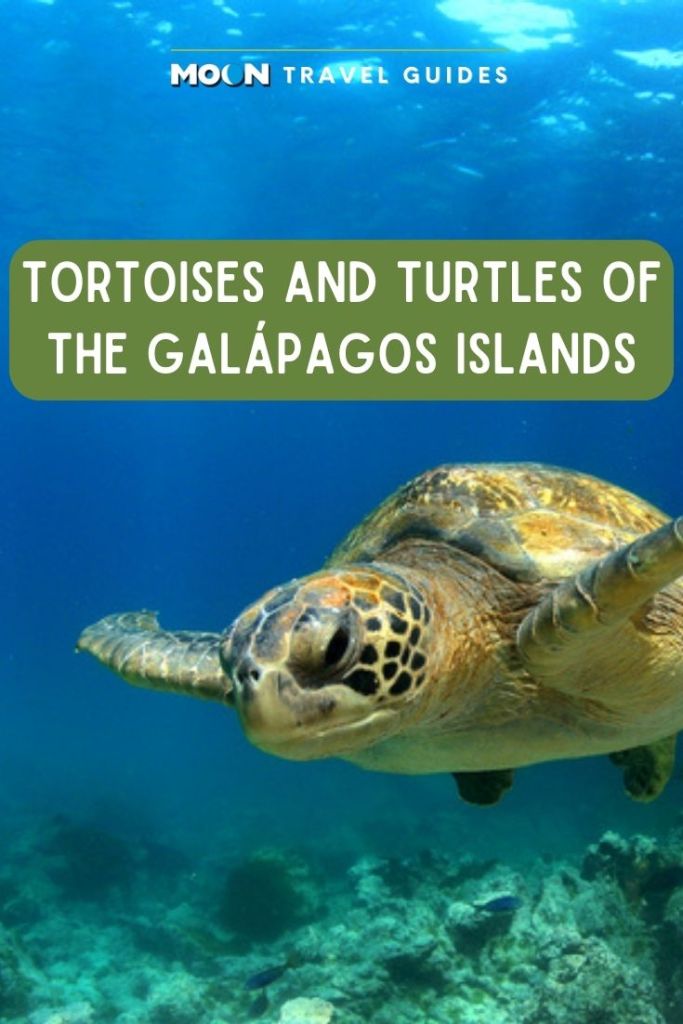

Sea Turtles

There are four species of marine turtles in the archipelago. The eastern Pacific green turtle, known rather confusingly as tortuga negra (black turtle) in Spanish, is the most common species. Also present but rarely seen are the Pacific leatherback, the Indo-Pacific hawksbill, and the olive ridley turtles. Sea turtles can be seen year-round throughout the islands.

Green sea turtles are rarely seen in large numbers, preferring to swim alone, in couples, or next to their young. They usually weigh 100 kilograms (220 lb) but can weigh up to 150 kilograms (331 lb). The females are bigger than the males and can grow to 1.2 meters (3.9 ft) long. They feed mainly on seaweeds and spend long periods of time submerged, even resting on the seabed and surviving without oxygen for several hours.

Both genders are polygamous, and several males often mate with the same female. Mating is particularly tiring for the female, who has to do most of the swimming while the male holds on.

Sea turtles must come ashore to lay eggs, and females often do this as many as eight times during the mating season, laying dozens of eggs each time. The female climbs the beach above the high water mark and digs a pit to lay the eggs before returning to the sea. If the eggs can evade the attention of predators, particularly pigs, rats, and even crabs and beetles, then the hatchlings emerge and make their way to the sea, where they may be gobbled up by sharks or even pelicans.

Despite the high mortality rate, green sea turtles thrive in the islands and spread far from the archipelago. Turtles marked in the Galápagos have been found as far away as Panama and Costa Rica as well as commonly off the coast of Ecuador.

Where to Spot Sea Turtles

With a little luck, sea turtles can be seen swimming all over the archipelago, but the best-known sites are Punta Vicente Roca and Los Túneles on Isabela, La Lobería on Floreana, and Gardner Bay on Española.

Related Travel Guide

Save for Later